Global container shipping outlook: pressure mounts amid flood of new capacity

Pressure on the container market after historic boom

The container shipping market has become used to cyclicality over the decades, and it experienced an unprecedented peak in 2021 and 2022 with record rates and profits for liners.

But with consumers starting to reduce their higher goods spending, against a backdrop of a global economy reeling from an inflation shock and rapid rate increases, the demand slowdown is intense. Consequently, spot rates on major trade lanes have quickly dropped. But it’s the subsequent wave of investment in new vessels that will become noticeable in the years ahead.

Container trade in contraction in 2023 but will pick up moderately in the run up to 2024

As container boxes contain food and non-food consumer products, but also capital equipment, semi-finished products and raw materials, it highly correlates with global trade. But container traffic has been more extreme recently. The empty container boom over the course of 2022 was already a signal of deteriorating market circumstances after a surge in consumers of goods and early ordering to secure deliveries. A combination of logical normalising of consumption and de-stocking led to declining volumes. European ports also faced a setback because of sanctions on Russia. Europe’s largest container ports of Rotterdam, Antwerp-Bruges and Hamburg – transhipment ports to Russia – have also seen a decline in container volume and figures since the first half of 2023.

The process of normalisation is still ongoing and will leave the full year, on average, in mild contraction despite a rebound at the world’s largest port, Shanghai, in the second quarter of 2023. Although the economic slowdown continues to weigh on perspectives, we do expect container trade demand to improve mildly from the second half of the year and return to about 3% growth in 2024.

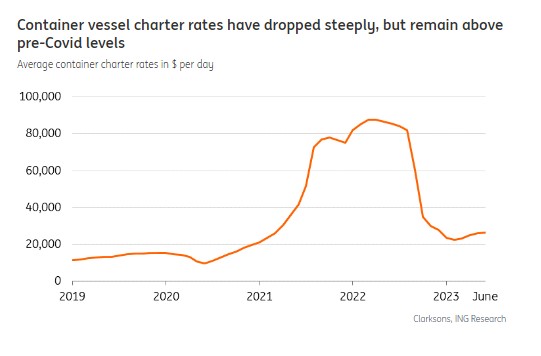

Container spot rates return close to pre-pandemic levels

The composite container index CCFI continued to slide in the first half of 2023 with pre-pandemic levels close. Corrected for inflation, spot rates on the Shanghai-Europe route are trading at lower real levels in June than pre-pandemic. Spot rates are still somewhat higher than they were four years ago, but the general price level in 2023 has gone up by more than 15% in Europe, meaning $2,000 per 40ft container is now close to $1,700 in real terms. This is also the case for Shanghai-US spot rates, although East Coast rates were stimulated by a shift from West to East Coast ports and restrictions on the Panama Canal. Rates from China to other parts of the world (such as South America) also show more resilience.

Six-to-12-month charter rates for container vessels and feeders in the range of 4,500-8,500 TEU have shown more resilience than spot rates and still trade significantly higher than they did pre-pandemic. And they seem to have bottomed out for now, as reiterated by the Harper-Petersen index. This may have to do with the expected recovery in the second half of the year as longer charters have shown to be weaker, but it’s nevertheless remarkable.

A lower order book for this segment and diversification of production could also support demand for smaller-size vessels. For longer contracts, charter owners may also still benefit from higher rates from the past two years.

Profitability drops steeply from peak levels

Overall container profitability level (EBIT) peaked at an exceptional 50% in 2022, similar to the year before. But that couldn’t last of course. Long-term average EBIT ranges have been a mere 1% with several negative years during the last decade. EBIT levels of the largest container liners (excluding MSC) dropped from more than 55% in the second quarter of 2022 to 17% in the first quarter of this year.

Locked-in contract rates with shippers lead to a delayed profit decline in 2023

More than 50% of container volume is being shipped under term contracts with shippers. For Maersk, this was even close to 70% for the full-year 2022. Most contracts closed at peak rates expire in the first half of 2023, leading to steep declines in new rates. Consequently, plummeting spot rates will gradually feed into total transport costs in the first half of 2023. The downward pressure of supply may even lead to negative margins returning in 2024, but capacity discipline and external effects will have an impact.

Flood of new capacity is making waves in a low tide

The prosperous years in container shipping sparked a surge in orders for new (large) container vessels. In March 2023, 27% of the installed fleet capacity was expected to be newly delivered between 2023-25.

Capacity on order is much lower than during peak levels before the financial crisis in 2008, but the fleet itself is also much bigger now. Given that the trend of the ongoing globalisation of supply chains is over, it may still be more challenging this time.

On the other hand, the container sector is more consolidated than it was 20 years ago. The three alliances of container liners are allowed to operate in Europe, at least until the expiry of the current block exemption in Europe and the UK on 25 April 2024 (2M will be dissolved in 2025, Ocean Alliance and The Alliance plan to continue to 2027).

It’s all about capacity in the upcoming years

The main driver of investments in new vessels is future demand, but most importantly fleet growth and more efficient (larger) vessels. More than 700 ships are expected to be delivered in 2023-24 and more than 150 in 2025. Some 45% of this is covered by Neo-Panamax size vessels (12,500-18,000 TEU) and another 20% by the largest sizes (ULCV). Feeder vessels (up to 3,000) make up just over a third of the ordered vessels and just 8% of capacity.

The push for sustainability and dual-fuel vessels have bloated the container vessel order book

The push for alternative fuels in shipping is strongest in the container segment, probably as it operates relatively close to consumers. According to shipping and trade data provider Clarksons, almost half of the total order book for new vessels consists of either LNG or methanol ‘capable’ or ‘ready’ dual-fuel vessels and these orders accelerated in 2022. Maersk ordered a range of 25 dual-fuel vessels able to run on methanol and is busy with partners creating supply in ports. Various liners including ONE-line, CMA-CGM and others will probably follow. LNG still makes up the largest fraction of alternative fuel ordered for vessels followed by methanol, but ammonia is also on the cards despite its toxicity.

Dual-fuel means that vessels are either equipped to run on alternative fuels, or that the vessel is already able to switch. In most cases, vessels can still burn fuel oil or switch to it, which provides flexibility, also in the light of price differential as a premium needs to be paid. In most cases, retrofitting vessels is not attractive. This means the surge in dual-fuel investment pushes capacity inflow up further. Find our analysis for synthetic fuels in shipping here.

Rates are fragile and could easily go lower in 2023 and 2024

The large new capacity inflow, in combination with faltering trade growth, could spoil freight rates, as new capacity won’t be absorbed by additional demand anytime soon. In addition, blocked capacity stuck around congested ports – taking out as much as 15% of capacity at its worse point in early 2022 – is increasingly being released as supply chain performance improves. Some new orders may be cancelled, but that is not expected to be massive as no one wants to lose out on efficiency progress per unit carried.

This means it all comes down to managing capacity now. The question is, how will container liners respond? So far, liners have been eager to attain market share. Occupation levels of vessels have already come down (to 75% in the first quarter) and freight rates have shown to be fragile in the second quarter and the decline could continue. Given that container liners are cash-rich, these circumstances can easily develop into a price war for a long time.

How to manage overcapacity (capacity discipline) – three options

Container liners generally have three options to stir capacity and reduce the supply overhang:

• Scrapping: A big question mark is how container liners will act in the demolition of older vessels. Near the end of the lifecycle, as older vessel values approach the scrapping level, shipping companies may decide to take out capacity. At the same time, liners will avoid capital losses as much as possible. Sustainability regulations could speed up demolition activity in the coming years, although it is not speeding up so far in 2023. Global shipping branch Bimco expects scrapping to reduce capacity by about 3% in 2023-24.

• (Super)slow steaming: Another option to manage overcapacity is slow steaming. Sailing speed figures show that container vessels have slowed down their speeds in anticipation of new vessel inflows. In the first quarter, the average speed came down to 13.8 knots, 4% lower than a year earlier. Limited further speed reduction is still possible without suboptimality. This means for instance that one vessel can be added to the Asia-Europe loop. Slow steaming will certainly not absorb the full capacity overhang but perhaps around 5-7% of it. Part of capacity management could also be to do more sailing around the Cape of Good Hope. This extends the trip to Europe by five-to-seven days and saves around $700/k of the Suez Canal passing fare for a large container vessel.

• Cancel (blank) sailings: During the pandemic, carriers learned how to manage capacity (within alliances) to balance supply-demand in the short run by taking out (‘blanking’) sailings because of a significant slowdown. This worked relatively well, although it also affected reliability for clients. Cancelling sailings in case of sinking occupation rates is logical; about 65% of costs in container shipping are variable. The issue is, however, if carriers stick to this amid mounting competitive pressure. Figures from Lynerlitica, which provides market intelligence for the container shipping industry, suggest that this hasn’t been applied that much in the first half of 2023.

Regional capacity deployment may be less impacted by overcapacity

Many ports across the world are nautically not equipped to receive the largest ULCV vessels. This is the case for ports in Brazil, India and other countries across Asia, for example. The Panama Canal isn’t accessible to them either. This means that routes outside of the main trade routes could be less impacted by overcapacity, although there will be cascading. As a result, the rate picture will differ for various routes. And container liners also have various regional specialisations. MSC and Hapag Lloyd are more diversified than some other large carriers.

Liner investments in becoming a full supply chain services provider may cushion performance

Container liners have been using strong returns to also invest in terminals and other logistics activities such as contract logistics and aircargo to provide integrated supply chain services to clients. In that sense, they compete with logistics services providers that have traditionally fulfilled this role for a longer time.

Large container liners including MSC, Maersk and CMA-CGM have invested in terminals, but they have also created their own air cargo fleets. This will allow them to diversify their exposure. After over $300bn total profit on sector level in 2021-22, profits will sink to a fraction of the previous years’ and the downward trend is expected to continue in 2023 as spot rates are back close to break-even levels and may push average profitability below par in 2024. However, the diversification strategies several large container liners including Maersk and CMA CGM, adopted may provide some cushioning for performance as margins of logistics services tend to be more stable and usally also larger than in container shipping.

How have three of the largest container liners performed?

Hapag-Lloyd

In May, Hapag-Lloyd reported weak international demand for container shipping services in the first quarter of 2023 as a result of the ongoing global inventory de-stocking, leading to declining volumes transported and lower freight rates. In the first quarter, the company’s shipping volumes were down 4.9% year-on-year and average freight rates were down 27.9% YoY. In the first quarter, Hapag-Lloyd reported revenue of $6bn, down 32.7% YoY, and EBITDA of $2.4bn, down 55.2% YoY. Hapag-Lloyd’s management commented that the results reflected a normalisation of the container shipping market environment after the elevated levels of freight rates during the past couple of years.

Going forward, a strong inflow of new container shipping capacity is expected to be partially offset by increased scrapping activity and slower steaming. However, Hapag-Lloyd anticipates that supply will still likely outpace demand in 2023 and 2024. Furthermore, the shipping company expects demand to remain soft until the destocking cycle is completed.

Hapag-Lloyd expects a gradual normalisation of earnings during the course of 2023, with transported volumes increasing slightly during the year, bunker prices declining materially, and freight rates decreasing significantly, with the resulting EBITDA down sharply year-on-year to $4.3-6.5bn, from $20.5bn in FY22.

AP Moller-Maersk

AP Moller-Maersk (Maersk) reported a decline in revenues and EBITDA in the first quarter year-on-year, in line with the weakening sector dynamic. Specifically, during the first quarter of this year, the shipping company had revenues of $14.2bn, down 26.4% YoY, and EBITDA of $4.0bn, down 56.3% YoY. While the first quarter results were significantly down year-on-year, the company still expects it to be the strongest quarter of the year. Maersk also referred to continued destocking driving demand lower and leading to the gradual market normalisation.

In conjunction with the first quarter announcement, the company reiterated its guidance for FY23, including expected global ocean container market growth of -2.5% to +0.5% and, assuming this scenario, EBITDA of $8-11bn, down sharply from $36.8bn in FY22.

CMA CGM

CMA CGM reported first-quarter 2023 results which continued the trend seen in the final quarter of last year. First quarter revenues were $12.7bn, down 30.2% YoY, and EBITDA was $3.4bn, down 61.3% YoY. According to CMA CGM, market conditions were challenging in the transportation and logistics industry, with freight demand slowing, leading to the aforementioned “normalisation” of spot freight rates.

In the company’s shipping segment, volumes transported were 5.0m TEU, down 5.3% YoY, and average revenue per TEU was $1,766, down 37% YoY. As a result, in the first quarter, CMA CGM’s shipping segment revenue was $8.9bn, down 40.3% YoY, and EBITDA was $3.0bn, down 64.3% YoY. The company attributed the decline in volumes shipped to the sharp fall in household consumption of goods in Europe and North America due to high inflation and the prioritisation of leisure and travel over physical consumption. It also blamed inventory adjustment in these regions, reducing imports, in particular, from Asia, while more vibrant activity in Latin America and Africa was insufficient to offset the decline on the main East-West routes.

In terms of outlook, CMA CGM acknowledges that risks remain given the soft macroeconomic outlook, while demand may potentially stabilise later in the year. At the same time, the company notes that new capacity due to be delivered over the coming quarters is expected to weigh on freight rates. Given this backdrop, CMA CGM anticipates that the first quarter will end up being the best quarter of this year.

Source: ING

Hellenic Shipping News Worldwide Hellenic Shipping News Worldwide, Online Daily Newspaper on Hellenic and International Shipping

Hellenic Shipping News Worldwide Hellenic Shipping News Worldwide, Online Daily Newspaper on Hellenic and International Shipping

PG-Software

PG-Software